Imagine being arrested and thrown in jail merely for expressing an unpopular opinion. Okay, now analyze and explain “hate speech.”

Campaign Finance Reform – A Primer

All attempts at Campaign Finance Reform in these United States have failed. ALL. Every single one of them.

If that sounds like exaggeration, just consider that attempts to limit the influence of money in politics is typically taught in history or civics classes as beginning (in earnest) shortly after the presidency of Andrew Jackson, the pro-slavery founder of the Democratic party whose administration ultimately produced the political “spoils system.” That would put us back to the mid- to late- 1830’s. Good ol’ “Honest Abe” himself was bankrupted trying to personally finance his first Senatorial campaign in 1858, so he had to rely upon businessman from Philadelphia and New York to finance his Presidential campaign in 1860. According to some historians, however, money was in politics from the beginning of the Republic.

In the United States, concerns over financing campaigns for public office have been around since before the writing of the Constitution. Candidates traded influence, power, and gifts, for constituents’ money and votes even before the dawn of the Republic. George Washington – later President, but at the time, a candidate for the Virginia House of Burgesses – bestowed upon the 391 voters in his district the “customary means” of winning votes: “28 gallons of rum, 50 gallons of rum punch, 34 gallons of wine, 46 gallons of beer, and 2 gallons of cider royal.” James Madison lost his reelection campaign to the Virginia legislature 20 years later because he refused to provide voters with the customary whiskey.

Gardner and Charles, “Election Law in the American Political System,” p. 637.

In 1867, just two years after the Civil War, the first legislative attempt at campaign finance reform appeared in a Naval Appropriations bill. It forbade government officials from soliciting (i.e. “shaking down”) Navy Yard workers for money to finance the ruling party’s election campaigns. This had become a routine practice in prior years. So routine was it that federal employees would have some portion of their pay directly “assessed” by the government to the Party’s re-election fund. The protections of the 1867 Navy yard workers were eventually extended to all civil service workers… (But not the rest of us, evidently.) The Presidential campaign of 1896 was so openly a case of dueling donors obtaining political promises from each Parties’ respectively well-financed candidates – William Jennings Bryan for Team Blue and William McKinley for Team Red – that the public began yelling for campaign finance reform… and here we are 120 years later. This brief timeline of attempts at reform shows just how fruitless they all have been.

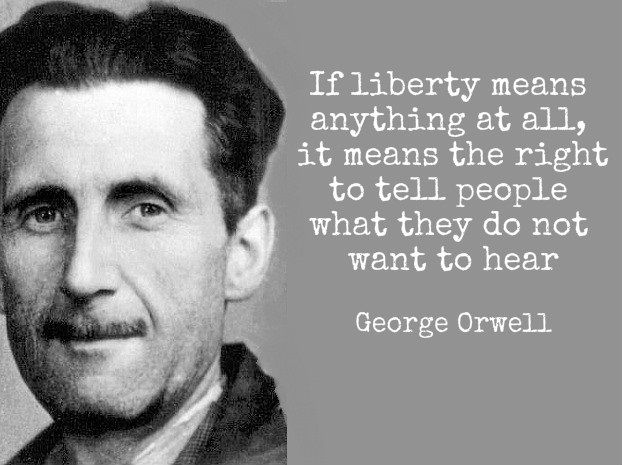

Modern, seemingly sophisticated attempts at campaign finance reform, by people from both political parties in Congress, have ultimately been set aside by Supreme Court decisions. While it may be unpalatable or politically inexpedient to say this, the Supreme Court’s rulings in these cases are very solid reads of the First Amendment… proving yet again the old adage that “sometimes even a blind squirrel finds a nut” or that “even a broken clock is right twice a day.” Lawsuits by public interest groups have ultimately failed to produce anything even close to a good result. Now the public feels so desperate for something to happen that they’ll embrace even nonsensical calls for reform by (of all people!!) Hilary Clinton. The much-ballyhooed, and almost totally misunderstood, case of Citizens United, 558 U.S. 310 (210) was about a non-profit movie company that made a film about then Senator Clinton. The Federal Election Commission agreed that the movie would be subject to a federal campaign finance law that would have imposed criminal and civil penalties on the movie company. That is to say, the law as it was made it a crime for a collection of people – using a corporate form – from expressing their political opinions, quintessential First Amendment conduct. Hard to imagine that the words “Congress shall make NO LAW” are ambiguous, but here we are, with a mountain of laws collectively regarding each and every one of the subjects specifically listed as exempt from regulation in the First Amendment.

Either We Are a Republic With a Charter To Be Faithfully Followed, or We Are Not.

Understanding How the (Legislative) Sausage Gets Made

To understand why campaign finance reform doesn’t work – and what simple fix would work – you have to understand some basic economics around how the political sausage gets made, so to speak.

First, you must know what politicians all know: there has only been one time in the last 42 years that the rate of re-election for Congressional incumbents dipped below 90% – that was 1974, when it was only 89.7%, a rounding of tenths away from being 90%. Muse on that for minute – Congress has had historically bad approval ratings – like below 20%, for decades, by any polling company. Everyone thinks Congress sucks; yet Congressional incumbents get re-elected over 90% of the time. It’s a near-certainty. Many people have speculated or offered reasoned opinions about this phenomenon, but I don’t really care about the “why” because the mere statistical truth of it is all that matters for my argument.

Second, we must make the rather short “hop” of faith and assume that politicians are at least as self-interested as the rest of us… one might humbly suggest that they are (perhaps) even a bit more self-interested than the rest of us, or make the claim that the job attracts the type, but I don’t need to prove that as crucial to my theory. Suffice it that my claim rests on what I believe to be a rather well-observed phenomenon about the self-interest of politicians. Lord Acton wrote an entire tract explaining this, but unfortunately no one reads it and all that we remember (if at all) is this quote: “Power corrupts, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” My own observation from many years of government service and being an American is simply that the government does not choose its prospective employees from some magical pool of magnanimous, morally benevolent, and personally-disinterested human beings. If you think I am incorrect, you’ve obviously never been to the Department of Motor Vehicles to register your car, or change the title, or correct a typo on a Vehicle Identification Number (VIN). Try to manage that over your lunch break and let me know how it goes; and ask yourself about how good the customer service is while you’re there.

The Currency of the Politician is Law – Legislation For Some and Against Others

Rep. Chuck Schumer (D, NY) explains how he can’t read, doesn’t understand, and doesn’t care about the 1st Amendment.

To the above facts we have to add some economics. In my opinion, the best way to begin to understand this is to ask a very simple question: if you were a legislator looking to raise some cash, what would you have to sell? (Think about it seriously for a moment).

ANS: Legislation. i.e. Laws.

Legislation is the only thing that a lawmaker can offer any prospective “buyer.” It is the medium of exchange (i.e. the currency) of the political class and a specific instance of the more general “Law of the Instrument.”* In return for a piece of favorable legislation, or a clause in the next omnibus bill – or exemption from cuts or regulation – political donors deposit sums into re-elections campaigns, or exchange different favors with lobbyists – the “middlemen” of the entire Money-for-Favor-for-Reelection Triangle.

If this seems unduly cynical, it shouldn’t be. If you have a friend who is a cop, who hasn’t heard of, or considered, asking him or her to “look into” a ticket…? Now magnify that onto a scale where instead of your hundred-fifty bucks plus court costs being at stake, it’s someone else’s multi-million dollar, multinational business and a piece of legislation that would ensure government contracts flowing that direction for the next 10 years. Or a promise to keep government regulators out of your business for at least your friendly Senator’s next 6 years of office. If all of this seems speculative or just too much to swallow at once, consider this quote right from the horse’s mouth, as it were:

You send us to Congress; we pass laws under which you make money…and out of your profits, you further contribute to our campaign funds to send us back again to pass more laws to enable you to make more money.

— Senator Boies Penrose, (R, PA) 1896 (quoted in Id., Gardner and Charles, p. 638.)

I always hear people complain about the influence of “corporate money” in politics and yet no one ever seems to consider that if their Senator wasn’t offering legislation for sale, the corporation wouldn’t be able to make a purchase. And it is in no way solely corporations buying-off politicians. Unions are at least as powerful and well-off as any corporation and billionaires with agendas sit on both the left and the right of the political spectrum. In fact, if we’re dealing in generalities, it is worth wondering: if corporations are filled with greedy, capital-obsessed Scrooges, why would any of those money-grubbers ever voluntarily give their money to a politician in the first place? To ask the question is to destroy the premise.

When you’re starting a company in your garage you don’t start by setting aside your political lobbying budget, then make whatever widget, software, computer, or other item that is the money-making aspect of your new venture. You first have to make something that a large enough number of people are willing to voluntarily pay you such that you have a growing enterprise, be it a successful song, an iPhone, the personal computer, or a rubber tire. Legislators don’t enter your mind until well down the road in the business cycle. Thus, perhaps it is enough to agree that legislators aren’t the unfortunate victims of a “system” that is foisted upon them. What Senators and Congressman do to fill the coffers of their re-elections campaigns is a perfectly natural, foreseeable byproduct of the funding of the political system.

Part Two explains how it works in greater detail.